As MU looks hard at diversity, the world’s first J-School also needs to revisit a ‘notorious act of racism’.

A student protester stands between tents set up in an encampment as night falls Monday, Nov. 9, 2015, on the University of Missouri campus in Columbia, Mo. The developments at MU call for a revisiting of a racist incident in the history of the Missouri School of Journalism, writes KCPT reporter and Missouri School of Journalism alum Mike McGraw. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

A student protester stands between tents set up in an encampment as night falls Monday, Nov. 9, 2015, on the University of Missouri campus in Columbia, Mo. The developments at MU call for a revisiting of a racist incident in the history of the Missouri School of Journalism, writes KCPT reporter and Missouri School of Journalism alum Mike McGraw. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Published November 19th, 2015 at 3:12 PM

In the wake of historic changes at my alma mater in Columbia, it seems as though everybody in a position of power there has been clawing for higher ground.

University administrators who were forced to resign don’t want to be seen as racist, maybe just clueless. The Board of Curators, which actually thanked those former leaders for their service, apologized for being “slow to respond.”

Now the university’s School of Journalism – from which I graduated in the early 1970s – has weighed in with a statement of its own.

In a recent letter, the school’s new dean, David Kurpius, reiterated that the J-School “stands for inclusiveness” and that “we want the school to be a welcome environment for people from different backgrounds, races, religions and sexual orientations …”

Kurpius announced that the school has hired an African-American adviser, and that he’s negotiating to hire “an additional African-American professor.” That would bring to four the number of blacks among the 80-member full-time faculty at the school.

Kurpius added that in 1988, the school offered what it called the nation’s first “multicultural course required of all students.”

I have no reason to doubt the new dean’s sincerity or the school’s recent accomplishments in this area. The fact is, with 8 percent of its Fall 2015 undergraduates reported as being African American and 20 percent minority overall, Mizzou does a better job than some other journalism schools, most likely because they work hard to recruit those minorities.

But the multicultural course Kurpius was touting was instituted only four years after the J-School finally – after nearly 50 years – addressed a notorious act of racism. And it’s a period I suggest, with all due respect, that the new dean revisit in light of what has happened in Columbia.

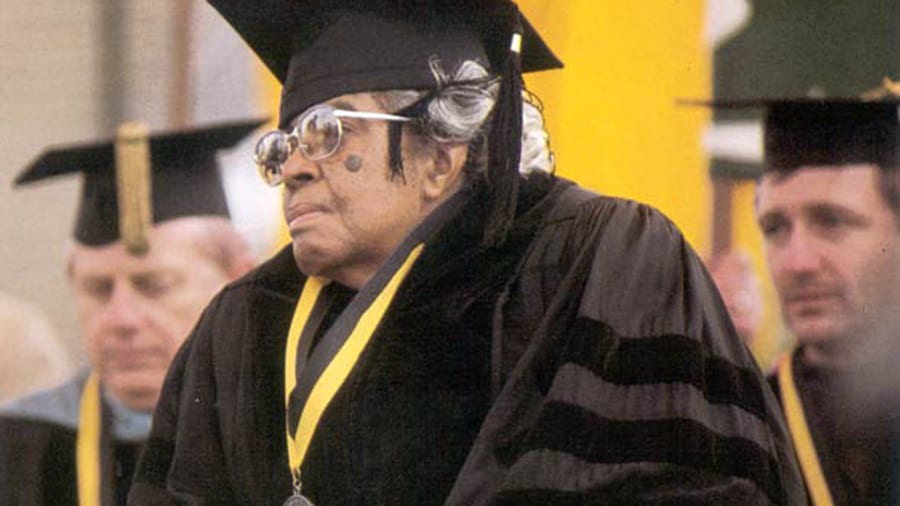

It wasn’t until 1984 that the J-School presented its highest award – the Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism – to an African-American woman named Lucile Bluford. A few years later, in 1989, the university gave her an honorary doctorate degree that she accepted, she said at the time, “not only for myself, but for thousands of black students” that MU had discriminated against over the years.

It was an attempt to “atone, far too late, for its sins” – according to a history of the school, “A Journalism of Humanity,” by journalist and biographer Steve Weinberg, a professor emeritus there.

By then Bluford, who died in 2003, had accomplished a lot for someone not considered worthy of a Mizzou graduate degree in journalism. She became a leading voice in Kansas City’s civil rights movement and helped make The Kansas City Call one of the nation’s largest and most important black newspapers.

Years earlier, in 1939, Bluford, a 28-year-old managing editor at The Call, was accepted by the J-School to do graduate work. She had already earned an undergraduate journalism degree from the University of Kansas.

But when she showed up in Columbia and they realized she was black, they turned her away and referred her to Lincoln University, a “separate but equal” college for blacks, which at the time offered no journalism courses.

Not one to give in easily, Bluford finally sued, and in 1941 the Missouri Supreme Court ruled in her favor and ordered MU to admit her. Rather than comply, however, the J-School shut down its graduate program, according to the State Historical Society of Missouri, claiming it had become dysfunctional because the majority of its students and professors were off serving in World War II.

“Our newsrooms are increasingly becoming employers that do not embrace the increasing diversity of our country …” –NABJ Vice President Deirdre M. Childress

A few times over the years I’ve informally suggested to several J-School faculty members that it might be time to do more than just give Bluford a medal and an honorary degree and be done with that ugly chapter in their history. Maybe it’s time, I suggested, that the school do something under Bluford’s name to encourage more African Americans to enter journalism.

Associate dean Lynda Kraxberger agrees. “Honoring Bluford now makes a lot of sense,” she said, especially in that donors have been contacting the school in the last week or so suggesting ways to recruit and retain more black journalism students.

But she added, “if we do something in her name, it might look bigger than scholarships or recruitment.”

And that’s a good idea. Blacks have always been woefully under-represented in the media – and that may be at least part of the reason the J-School has so few black faculty members.

Indeed, according to data compiled by the Pew Research Center last year, the 2008 recession that sparked thousands of layoffs at newspapers around the country, was harder on already-under-represented African-American journalists than it was on whites.

According to a recent study highlighted by the National Association of Black Journalists, 441 newspapers nationwide had no minorities whatsoever on their full-time staffs.

“Our newsrooms are increasingly becoming employers that do not embrace the increasing diversity of our country and this failure is often reflected in dismal coverage of the black community and all communities of color,” an NABJ Vice President, Deirdre M. Childress, said several years ago.

Perhaps Dean Kurpius can insure that the legacy of Lucile Bluford and her experience at the world’s first journalism school can help change that.