A City Haunted by Ghost Water Leaking Water Adds Millions to Ratepayers’ Bills

(Jesse Howe | Flatland)

(Jesse Howe | Flatland)

Published February 15th, 2017 at 2:53 PM

It first bubbled up a year ago as a steady stream at the edge of Harry Ellis’ well-kept lawn.

It flowed across the nearby roadway north of the river and splattered mud on passing cars. In the winter, it formed an icy glaze.

The people from the city came. They dug down to their pipes and strained to hear rushing water but never found its source.

A year later, the soggy squatter remains but stays mostly hidden, diverted to a drain under the roadway.

From there, it flows a few hundred yards downhill toward the place it may — or may not — have come from in the first place: the Kansas City water treatment plant.

Ghost Water

Like a lot of the water Kansas City pumps to its customers, you might call this ghost water.

We can’t pinpoint precisely where it came from, and we aren’t sure where it all goes. But we know there’s a lot of paranormal activity.

Billions and billions of gallons.

Pervasive leaks and long delays in repairing them are nothing new in Kansas City.

They have driven motorists and homeowners to distraction for years and left the city’s Water Services Department with a hard-to-shake reputation as a dysfunctional bureaucracy.

What is new is that the department appears to be trying to get a handle on all this ghost water and figure out where it’s going.

In fact, a 2015 water loss audit obtained by Flatland under an open records request offers these rough estimates:

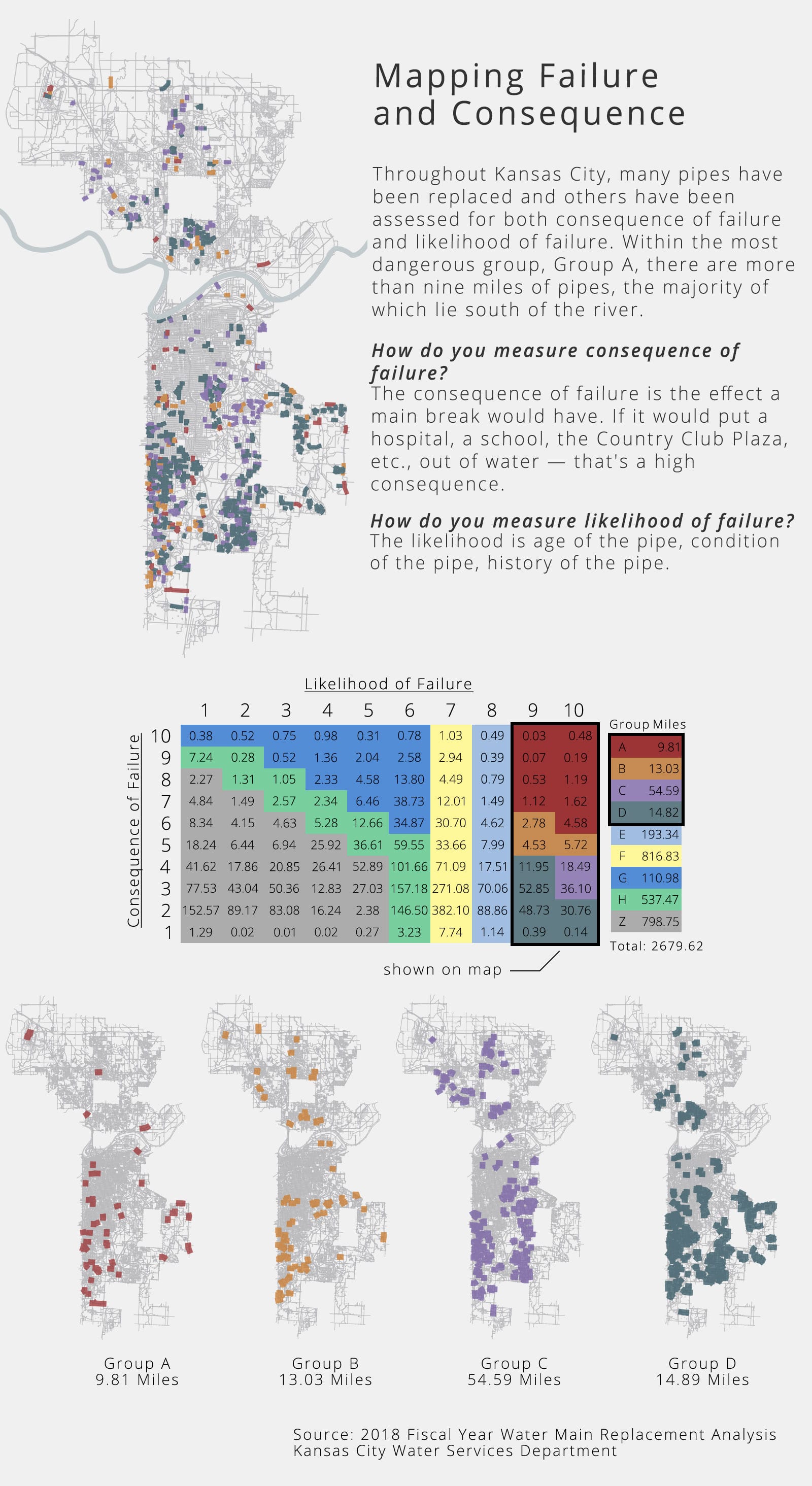

Of the 28 billion gallons of treated water Kansas City pumped into its distribution system in 2015, a third — 9.15 billion gallons — went missing.

That’s enough ghost water to fill 14,000 Olympic-size swimming pools.

Water department Chief Financial Officer Sean Hennessy agrees those are big numbers and said water utilities around the country have been reluctant to discuss them.

This is part of what experts call “non-revenue water.” In fact, the audit estimates that more than 40 percent of the water Kansas City pumped in 2015 did not generate any revenue for the city.

A 2016 update is expected, but department officials first want to try to improve the accuracy of their raw data. And as the accuracy improves, the amount of ghost water could go up or down by billions of gallons.

For now, however, “this is a system that has substantial losses,” said Ed Osann, a water efficiency expert who reviewed the audits for Flatland.

The value of the lost water should be the least of the city’s worries, Osann said. Leaky systems can cause flooding, require expensive repairs and allow contaminants into drinking water.

Osann, a project director for the Natural Resources Defense Council, added, “I would say the system gets some credit for candor here; they are not sugarcoating the situation.”

While leaks are clearly part of the problem, it’s more complicated than the water percolating near Ellis’ house and all its shadowy siblings haunting 2,800 miles of city pipelines.

Ghost water also includes water used when city crews flush water mains or when the fire department checks its hydrants.

Faulty meters and unmetered water are also likely culprits.

For example, millions of gallons of ghost water flow through the city’s many fountains each year. The Parks and Recreation Department currently gets that water for free, but it is expected to start paying for it soon.

Water also can be lost through theft. In fact, department officials believe they are losing significant water in abandoned houses and at rental properties where landlords or tenants have simply removed water meters.

City officials have yet to collect and analyze all the data they will need to put a finer point on the problem.

In the meantime, it’s clear that ratepayers are bearing at least some of the cost of all this ghost water, but it’s hard to say for sure how much.

Depending on how you parse the numbers, it could be as much as $24 million a year, or $133 per customer each year, according to experts who viewed the audit at Flatland’s request.

A water department spokesperson responded, “While we disagree with the $24 million dollar loss revenue number, we acknowledge that our water loss is higher than it should be. We estimate our cost of this lost water could be as high as half that amount.”

Either way, it’s clear that ghost water has contributed to the quadrupling of the combined water, sewer and stormwater bills, which now average $110 a month.

And it’s one reason the department needed revenue from a $500 million water infrastructure bond issue passed in 2014.

The good news here is that the gusher of new revenue — and the city’s burgeoning effort to corral ghost water — puts the Kansas City Water Services Department out front when it comes to repairing the city’s deteriorating infrastructure.

For example, the city has recently replaced nearly 100 miles of water mains.

The bad news is that it may not know where best to spend all this new revenue until it tracks down all this ghost water.

Indeed, the only way to banish all the demons that haunt the water system is to collect more and better data and perform what experts call a Leakage Component Analysis.

North Versus South

The Kansas City water department was established in 1873, and some pipes laid under the City Market the following year are still in use today.

Indeed, the city audit shows that the vast majority of ghost water haunts the area south of the Missouri River, where the oldest pipes, valves and meters are located.

Of the 11 billion gallons of water the city pumped in 2015 — but which no one ever paid for — 9.5 billion gallons of it disappeared south of the river.

By comparison, only about 350 million gallons escaped from pipes north of the river.

One reason for the vast difference, Hennessy said, is that as the city expanded south of the river, it inherited older water systems. In some cases, the water department doesn’t even have maps showing where water mains in those areas are located.

A small portion of these leaks reveal themselves on the surface, but the vast majority remain hidden in their subterranean haunts.

As any amateur plumber knows, fixing leaks is frustrating, even if you can see them. But imagine that the leak isn’t just somewhere inside your home.

Imagine instead that it is somewhere — indeed a whole lot of places — across hundreds of square miles.

We’re not talking about a couple of toilets and some sinks. We’re talking about 2,800 miles of pipes, 35,000 valves, 23,000 fire hydrants and 18 pumping stations.

The Kansas City water supply system is spread across more than 300 square miles.

Exorcising the Ghosts

The science of water loss control has emerged in recent years from concerns about disappearing water supplies and the multibillion-dollar problem of pumping ghost water.

It has gained currency in arid regions, but Midwestern states have done little to encourage water utilities to get a handle on it.

According to the American Water Works Association, nationwide the average water utility pumps around 25,000-30,000 gallons of non-revenue water per connection per year. That costs an average of $30-40 per ratepayer.

Comparisons are tricky. But even with those limitations, the ghost water problem here appears to stand far above those of other cities, with Kansas City producing about twice the average amount of non-revenue water.

Unlike Kansas City, some cities have agreed to allow their water loss audits to be posted online. The data is still sketchy, but the comparisons can be stunning.

While Kansas City loses a third of its water, Cincinnati loses about 6.8 billion of the 34 billion gallons it pumps — about a fifth.

In arid areas, where water is more valuable, the difference is much greater. The Las Vegas Valley Water system, for example, which is newer than ours, loses just 3.6 billion of the 104 billion gallons it pumps — about 3 percent.

Diary of a Leak

Not all leaks are the same, but the ghost water outside Harry and Penny Ellis’ house north of the river may be instructive.

According to city records, there had been a leak in the area in the past. In fact, the water department is still struggling with a backlog of more than 4,500 repair orders citywide.

City documents show that this new leak made its first appearance last Feb. 23. When a city crew showed up, water was bubbling out of the ground at a “stream pace,” but the crew couldn’t find its source.

On Feb. 29, the city took a sample of the water to try to determine whether it had been treated by the city — meaning it was likely leaking from city pipes.

The Ellises again reported the leak on March 3, after which city workers noted that a lab test “indicated” it was not city water and that it appeared to be “water runoff/natural spring.”

The Ellises said they’d never observed groundwater in the area before. And a local lab that analyzes water samples told Flatland that the results of such tests can be unreliable because groundwater can contain some of the same substances found in treated water.

Charles Spencer, a consulting geologist who checked the area at Flatland’s request, said that, based on his preliminary visual inspection, it doesn’t appear to be groundwater.

Spencer said in his report that “a sudden appearance of water seepage — when none has been present before — is usually indicative of a water leak rather than natural groundwater discharge.”

Another complaint came in March 28, saying that the city had never repaired the road from earlier attempts to locate the leak and that a gravel pile was blocking half the street.

City workers completed the road repairs, but neighbors called again on June 24 to say water started leaking through the city’s brand-new asphalt patch the day it was laid.

City crews reported it as a new leak in mid-August. Calls kept coming in, and in late September one resident noted that he was concerned that the street would “ice over and cause accidents.”

That’s when crews set up a temporary sign warning of ice on the road.

On Nov. 4, records show, a city worker noted that “this location has been re-investigated quite a few times and WHAT IS NEEDED is a French drain put into the area to control the water flow.”

That allowed the water department to transfer the problem to someone else — Public Works. And that’s what they did.

In fact, city records show that over the past three years, Public Works had built at least ten of these drains at the request of the water department.

The drain near the Ellis house was installed in December, and the water — wherever it came from — began flowing down the hill toward the city’s water treatment plant.

Which of course is where all our ghost water begins in the first place.

— Mike McGraw is a special projects reporter for Flatland. Follow his stories online at FlatlandKC.org and @FlatlandKC.

GHOST WATER NYMTH

This Was A VIDEO CREATED BY PAUL THOMUS

A Beautiful Young Lady Was Visiable As Long As She Was Yet. She Lived in An old Hotel Over A Spring.

I Had The Video Once Then I lost itt.