Take 5 for Your Health A Clickable Roundup Of Health News From Our Region For The Second Week Of December

At 22.15 percent, Clay County, Kansas, has the highest recorded rate of Alzheimer's among Medicare beneficiaries of any county in the United States. (Photo: Andy Marso | Heartland Health Monitor)

At 22.15 percent, Clay County, Kansas, has the highest recorded rate of Alzheimer's among Medicare beneficiaries of any county in the United States. (Photo: Andy Marso | Heartland Health Monitor)

Published December 8th, 2015 at 7:55 AM

North-Central Kansas County Copes With Soaring Alzheimer’s Rate

Almost every day, Jay Mellies leaves his home in Clay Center and drives about 20 miles north to visit his wife at a nursing home in neighboring Washington County. Some days when he comes in she tells staff, “I don’t know that guy.” Then she smiles. It’s a joke, but Mellies knows someday it may not be. His wife has Alzheimer’s disease.

If at some point she no longer remembers him, he will continue to come, nearly every day, to read to her and listen to her favorite music. They’ve been married 55 years, after all, and he believes others would do the same for their spouses.

“There’s no way you can just walk away and throw them under the bus,” Mellies said. “You’ve got to be there.”

There are about 5.3 million Americans with Alzheimer’s, almost all of them 65 and over and on Medicare. That number is expected to grow by almost 2 million in the next 10 years as the aging of the baby boomer generation puts more Americans at risk for the memory-sapping illness.

Clay County, population 8,406, is at the tip of that spear.

According to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 392 of the north-central Kansas county’s 1,770 residents in traditional Medicare had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or a related form of dementia as of 2013. At 22.15 percent, that was the highest recorded rate of Alzheimer’s among Medicare beneficiaries of any county in the United States — just above Florida’s Miami-Dade County.

It’s challenging to pin down why the Kansas county stands out statistically.

Most other counties have more people in Medicare Advantage, privately run plans whose members are harder to track. That could be a factor.

Researchers also believe there’s a genetic component to Alzheimer’s. So if a handful of large families in a lower-population area like Clay County are predisposed to having the disease, it could affect the Alzheimer’s rate.

Alzheimer’s is a tricky diagnosis, and Clay County’s doctors might be better at spotting it than others. The county also has lots of senior housing. According to census data, almost 22 percent of Clay County residents were 65 or over in 2014, compared to 14.3 percent in Kansas as a whole.

Rankings aside, about 5 percent of the population in Clay County has Alzheimer’s or a related form of dementia, which is triple the national rate. Other Kansas counties — all low-population counties with aging residents — aren’t far behind. More than 4 percent of Trego County residents had Alzheimer’s or dementia as of 2013. In Gove County the rate was about 3.7 percent, and in Logan County it was about 3.5 percent.

There will be financial consequences as the Kansas population continues to age and the Alzheimer’s rate grows. A recent study found that the health care costs for treating people with dementia in the last five years of their lives are greater than any other illness.

But Clay County is finding ways to cope.

— Andy Marso is a reporter for KHI News Service in Topeka, a partner in the Heartland Health Monitor team.

Kansas Foster Care Official Involved In Same-Sex Adoption Controversy Resigning

The man who oversees the state’s foster care program is retiring, a spokesperson for the Kansas Department for Children and Families has confirmed.

Michael Myers, a former Topeka construction executive who has worked in several positions in the child welfare agency under Gov. Sam Brownback, will retire at the end of December.

DCF Secretary Phyllis Gilmore named Myers director of prevention and protection services in December 2014. He replaced Brian Dempsey, who abruptly left the agency along with Kathe Decker, former deputy director for family services.

Myers is not a high-profile official, but some critics of the agency say he is among those responsible for what they believe has been a concerted effort to prevent same-sex couples in Kansas from adopting children.

Theresa Freed, a spokesperson for DCF, said there is no connection between Myers’ retirement and the emerging controversy about the agency’s adoption policies. No one has yet been named to replace Myers, Freed said.

— Jim McLean is executive editor of KHI News Service in Topeka, a partner in the Heartland Health Monitor team.

Kansas City Health Foundation Could Get $434 Million In Damages From HCA

The Health Care Foundation of Greater Kansas City is looking at a potential windfall that could add hundreds of millions of dollars to its coffers, vastly expanding the pool of money it has to fund and promote community health programs.

Although legal appeals could delay its receipt of the money for several years, the foundation’s long-running lawsuit against local hospital giant HCA Midwest Health is coming to a head. And court documents show HCA is on the hook to the foundation for at least $319 million and possibly as much as $434 million.

The foundation, whose mission is to fund community health programs in the Kansas City area, was created with proceeds from the $1.1 billion sale in 2003 of Health Midwest’s hospitals to HCA. Those hospitals included Menorah Medical Center, Overland Park Regional Medical Center and Research Medical Center.

About six years after the sale, the foundation sued HCA over what it said was the company’s failure to fund hospital improvements and charitable care it agreed to in connection with the sale. In 2013, Jackson County Circuit Judge John M. Torrence concluded that HCA had not met its capital commitment and awarded the foundation $162 million. A later forensic accounting found that HCA owed another $78 million on top of that. In October, Torrence directed both sides to jointly draft a proposed final judgment for him to sign. There was just one problem: They couldn’t reach agreement on two significant, if somewhat legalistic, issues.

Torrence’s ruling won’t spell the end of the case, now more than six years old. HCA has reserved the right to appeal. The company disputes that it reneged on its commitments and further questions whether the foundation had standing to bring the lawsuit in the first place. In other words: This case is likely to continue for years to come.

Editor’s note: The Health Care Foundation of Greater Kansas City provides funding for Heartland Health Monitor.

Dan Margolies, editor of the Heartland Health Monitor team, is based at KCUR. You can reach him on Twitter @DanMargolies.

Gene editing designer babies would be ‘irresponsible,’ says international scientific committee

A committee of the world’s leading scientists has called the clinical use of gene editing technology on human reproductive cells — sperm or eggs — as “irresponsible” until confirmed to be safe. The committee, however, stopped short of calling for a full ban on research into gene editing technology, which has been billed as a possible cure for heritable diseases like Tay Sachs, sickle cell, Huntington’s or cystic fibrosis.

The summit is the latest landmark in an eventful year for human gene editing. In April, Chinese scientists at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou reported that they had tweaked human embryos with an emerging genetic tool called CRISPR-Cas9. CRISPR-Cas9 is like gene editing with a missile guidance system. The technique uses an enzyme from bacteria — Cas9 — to target and edit a sequence of DNA with very high precision.

The result was a media storm and public debate about the ethics of so-called “designer babies.” One issue is CRISPR-Cas9, like other methods of gene editing, can exhibit off-target effects, where an unintended sequence of DNA is altered. Even though CRISPR-Cas9 is one of the best marksmen to-date in terms editing, an off-target mutation in a reproductive cell opens the door to a heritable mutation being introduced into society. Soon after the Sun Yat-sen results, the U.S. National Institutes of Health banned funding for research that edits human embryos.

— Nsikan Akpan and Alexandra Sarabia for PBS NewsHour.

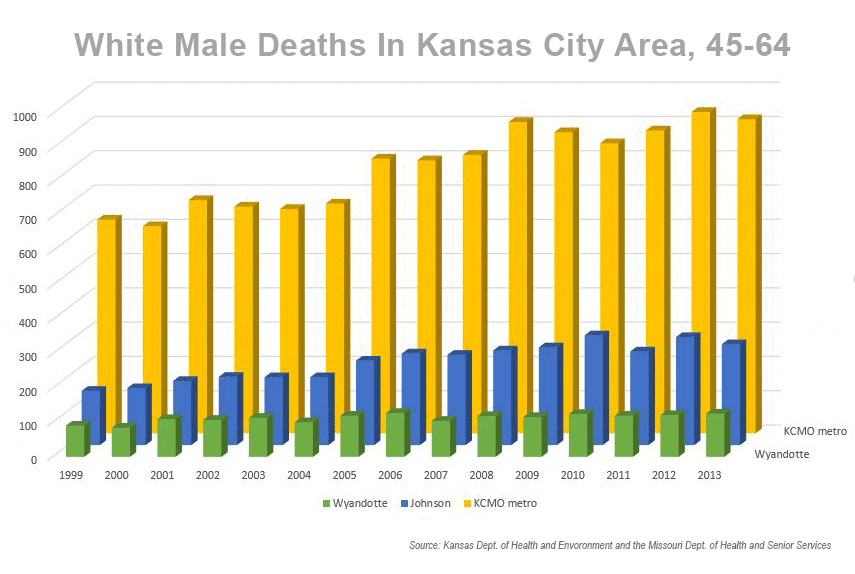

Kansas City Data Largely Tracks Rising Death Rates For Middle-Aged White Men

A much talked-about study by Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, who won the Nobel Prize for economics last month, found a spike in the death rate for middle-aged white Americans between 1999 and 2013, specifically those with a high school education or less.

That came as a big surprise to many health experts because the mortality rates for other demographic groups in the United States have been falling. Higher suicide rates, alcohol and drug abuse appear to account, at least in part, for the increase among middle-aged whites, but it’s not clear why this group – and not others – have been disproportionately affected.

Various explanations have been advanced for what New York Times columnist and Nobel laureate Paul Krugman termed “this epic of self-destructive behavior.” Krugman said Deaton’s suggestion that middle-aged whites have “lost the narrative of their lives” was a plausible hypothesis. Another New York Times columnist, the conservative Ross Douthat, proposed that members of this group may have lost their “sense of meaning and purpose.”

Whatever the explanation, we decided to see if local mortality data track Case and Deaton’s finding. We looked at the data for non-Hispanic white males, the subset with the highest mortality rates, in Johnson and Wyandotte counties on the Kansas side and in metropolitan Kansas City on the Missouri side.

Our comparison with Case and Deaton’s data is imperfect because they looked at whites 45 to 54 years old and the data we obtained was for white males between 45 and 64 years old.

Still, the age range was close enough. And what we found largely correlates with Case and Deaton’s conclusion, even after population increases are taken into account. Although the death rates fluctuated from year to year, the data sets for KCMO and Johnson County do show an overall spike in middle-aged white Americans’ mortality from 1999 to 2013.

The exception, curiously, is Wyandotte County. We say curiously, because Wyandotte County has some of the poorest health outcomes of any county in Kansas. The needle barely moved between 1999 and 2013.

That’s a cheering result for a county that has been working hard to improve its population’s health. Maybe those efforts are beginning to bear fruit.

— D.M.

Heartland Health Monitor is a reporting collaboration among KCUR, KCPT, KHI News Service and Kansas Public Radio focusing on health issues in Kansas and Missouri.