curiousKC | How the People Who Are Native to KC Lived, and Why Their Story Has Been Erased ‘Who were the Native Americans that first lived in the KC area?’

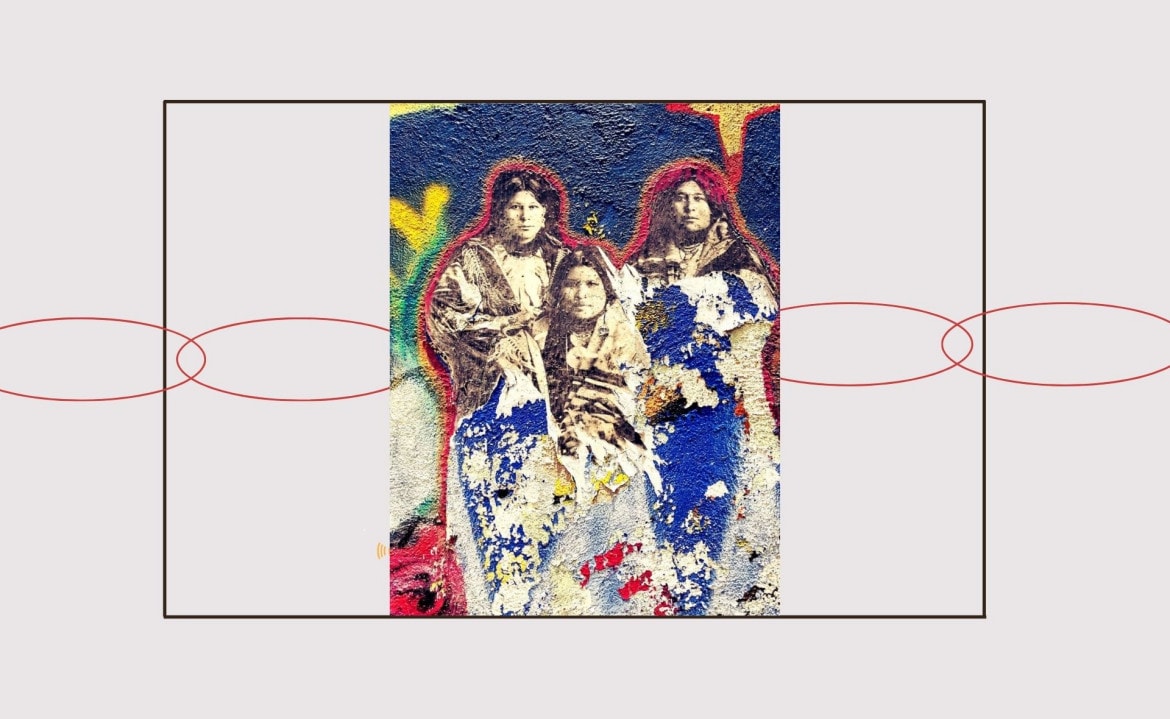

A collage of a Osage Nation mural in Fairfax. The photo was taken by Jimmy Beason II. (Vicky Diaz-Camacho | Flatland)

A collage of a Osage Nation mural in Fairfax. The photo was taken by Jimmy Beason II. (Vicky Diaz-Camacho | Flatland)

Published November 29th, 2021 at 4:50 PM

Kansas City’s story doesn’t begin with European fur traders who overtook Native American land. But that’s how it’s often taught.

We’ve seen it in elementary school pamphlets and high school textbooks, even in historical society websites. That’s why the following curiousKC question has taken us on an illuminating trek through history: “Who were the Native Americans (who) first lived in the KC area?”

Jimmy Beason II, who is on the faculty at Haskell Indian Nations University and a citizen of Osage Nation, which includes multiple tribes, helped us fill in the missing pieces to the story of Kansas City’s people.

Beason, who wrote a children’s book of Native history, explained that in Wazhazhe, the Osage language, Kansas City was known as Nishodse Tonwon or “smokey water.”

The Osage Nation once dwelled in what is now western and central Missouri, as well as eastern Kansas. But the land was more than just home, a place to reside.

To his people, Beason said, the land and its features were like a family member.

“In that area in particular the relationship to the land is one of recognizing the land as a relative and then recognizing all the other beings on that land as relatives,” Beason said.

But the European colonizers who forcibly procured that land didn’t acknowledge that viewpoint. Beason said Osage people, along with other nations, were not considered when the United States bought their lands from France through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Osage peoples were known for “village-based agriculture and nomadic bison hunting,” according to Britannica.

These practices were central to their survival. Osage cultural origins were rooted in the land around them. It informed their traditions, their economy and cosmology.

The spiritual and physical connection the Osage had to the land contributed to their strong culture. But this would be disrupted by European colonization and efforts to suppress Native tradition and eliminate military resistance.

A combination of factors would scatter and, later, displace Osage people.

First, in 1819 Congress paid Christian missionaries $10,000 to “civilize” Indigenous peoples. In other words, they were paid to impose their own ideas, religion and customs, which played out in Indian boarding schools. Children were taken from their families and stripped of their traditional clothing.

These practices forcibly severed Native children from their cultural identities.

Next, came a domino effect of policy and a disregard for heritage.

The Louisiana Purchase marked the start of westward expansion. But, the Indigenous peoples never consented to the “transaction” that would quickly lead to their forced migration.

Moreover, Europeans manipulated and pitted certain tribes against each other. Eastern tribes, which hd been displaced already by early settlers, sought new land for their people.

So, once the land was signed over to the U.S. government, the Osage not only lost their home but also food resources and the connection to what Beason called “cosmology.”

“That’s one way in which Osage, not only Osage but different tribal nations, their self-determination and autonomy has been violated,” Beason said. “No Native nations collectively agreed to say, ‘You can have this land’.”

Later, the government imposed the idea of sovereignty on the tribe, getting appointed leaders to sign away the land.

“Well, sovereignty even within native communities, that’s kind of a contentious term because sovereignty as an idea, as a concept, was something that was devised by the colonial governments,” Beason said. “Looking at self-autonomy and self-determination (for) Native people, essentially, we have to look at how our sovereignty, our self-determination, has been undermined in various ways.”

“No Native nations collectively agreed to say, ‘You can have this land’.”

Jimmy Beason II, faculty at Haskell Indian Nations University, author of “Native Americans in History: A History Book for Kids” (Sept. 2021) and a citizen of Osage Nation

Not only were they pushed out of what became Missouri, Osage citizens were also punished for returning to what was once their home. After Missouri became a state, Osages who attempted to cross back could be attacked and killed.

“Just for going into their ancestral lands,” Beason said. “And the white settler population wouldn’t get in trouble for it.”

The same fate would meet the Osage who tried to re-enter Kansas after the tribe was moved yet again down to Oklahoma, where it still resides today.

For the Osage, the land and its features are vital to their culture. The Osage formed clans informed by certain geographical features, animals and plant life in the region. Clans were like a network. Each clan’s particular geography determined responsibilities within ceremonies.

“All those were based off the animals and the plant life found in places like Missouri and eastern Kansas and upper Arkansas,” Beason said. “That was the main spot for the Osages.”

When forced to move and adapt to colonized ways, some of these clans died out. Beason said it meant certain ceremonies could no longer be performed by the Osage people because its performers were gone.

The buffalo, the main food source of the Osage and many other nations, had been driven from the land or slaughtered. The people were forced to turn to government subsidies to survive – creating a negative stereotype perpetuated by the government.

Beason explains that these experiences influenced how tribes like his evolved. The pressure to assimilate forced them to adjust to colonial customs. It wasn’t because they wanted to, he says, but because they were “basically being in a constant state of warfare.”

He added: “They had to change their worldview, and the way that they had to raise their children, and the way in which they had to conduct themselves, really forced them to be more pliable to U.S. demands.”

Thus, some ceremonies were abandoned. That impacted language loss because families were forced to adjust to different subsistence living, Beason said.

Their whole economy shifted as the slaughter of the buffalo deprived tribes of their primary food source.

“So they had to turn to the government for, like, handouts and things like that,” Beason added.

Looking around us, names like “Shawnee” or even “Missouria” reference the Native Americans whose land we’re currently on. While Osage territory today is still located inside of the nation’s original land, the move out of Missouri damaged the nation’s life and culture.

“Our present place in Oklahoma isn’t outside of our ancestral territory too much,” Beason said. “We’re technically still within our land base, but when you think about Missouri as historically, where most of the cultural cosmology was developed, of course, that’s going to have a devastating effect on the way that they conduct themselves (and) anything about the clan relationships that were broken up.”

It was a struggle to find a place to build a new home after they were stripped of their ancestral lands. Beason said eastern tribes spurred a lot of the violence and also initiated forced migration.

They, too, fought for a new home, but were serving also as a proxy army to the government who wanted the land cleared of its native people.

Christianization and ministry was another contributing factor to diminishing Osage culture.

“There was a very concerted effort on the part of the government to use Christian missionaries to kind of, again, change their cultural identity, change their cultural outlook,” Beason said.

The effects of cultural change are felt even today and taught in schools. In Missouri, particularly, there is a lack of history around the Osage Nation.

Beason said this happens with native groups around the nation. Erasure is, he added, “pretty much standard American colonization.” He said educational curriculums in U.S. schools prioritize colonial history above all other narratives. That is one way to continue the cycle of demeaning and minimizing the Indigenous presence.

“You would think that that would be the place where most people in the country … would understand and know about the Indigenous people, whose land the school now sits upon,” he said. “But they don’t, they don’t talk about that at all.”

The story of Kansas City includes the people who inhabited, nurtured and lived with this land. It’s the story of people who still very much exist. This is why people like Beason work actively to preserve their ancestral histories and pass that down one way or the other to the next generation.

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Vicky Diaz-Camacho covers community affairs for Kansas City PBS.